In Little Nightmares, the towering, crooked environments of The Maw do more than simply host puzzles and monsters—they speak. Through its surreal and decaying architecture, the game tells a story of oppression, consumption, and isolation. Every corridor, kitchen, and ventilation shaft whispers part of Six’s story without uttering a word. This article will explore how to interpret the architectural storytelling in Little Nightmares—how the design of its spaces communicates fear, social commentary, and psychological states. We will move chronologically through the game’s progression, uncovering the symbolic meaning of each area and how architecture becomes the game’s most silent narrator.

The Foundation of Fear: Setting as a Living Entity

The first impression of Little Nightmares comes not from characters, but from its spaces. The Maw’s architecture feels alive, pulsating with slow dread. Each hallway is constructed with uncanny asymmetry—ceilings that slope, furniture too large for Six, and lighting that stretches shadows like living things. This warped physicality makes The Maw seem sentient. It watches. It breathes.

Under the surface, the game’s architecture establishes a tone of domination versus smallness. The scale difference between Six and the environment constantly reminds the player of powerlessness. This imbalance mirrors the central theme of childhood vulnerability, where the world feels both too big and too cruel to control.

The level design also uses repetition to create subconscious anxiety. Narrow ventilation shafts lead into cavernous chambers, forcing the player to oscillate between safety and exposure. This rhythm of compression and release mirrors the emotional push and pull of fear itself—a masterclass in architectural pacing.

The Nursery of Shadows: Interpreting Early Spatial Design

The opening area, often referred to as The Prison, introduces Little Nightmares’ most haunting architectural motif: childhood confinement. The environment feels like an orphanage turned into a factory, where toys and cages coexist. The rooms are oversized and empty, evoking a child’s memory of being trapped in adult spaces.

The visual grammar of these early rooms—tiny beds, hanging cages, dim lamps—suggests an institutional past. It’s unclear whether this place was once for children or if it merely imitates that idea, but that ambiguity feeds the horror. The game uses environmental storytelling to communicate trauma: a world that imitates care while concealing cruelty.

Architecturally, The Prison trains players to navigate fear spatially. You learn to trust hiding spots, memorize routes, and anticipate patterns of danger. In doing so, you engage with the environment as both captor and companion—a duality that defines the rest of the game.

The Janitor’s Domain: Architecture as Predation

The transition to the Janitor’s section marks a tonal shift from institutional horror to predatory architecture. The Janitor’s long arms and limited vision create a gameplay loop based entirely on sound and space. His domain—cluttered rooms, wooden floors, and narrow hallways—is designed to amplify every creak and thump.

Here, Little Nightmares uses architecture to weaponize sensory experience. Every floorboard is a trap, every wall a possible echo. The game teaches players that movement and architecture are inseparable; you feel the building as you navigate it.

In symbolic terms, the Janitor’s environment represents sensory distortion—a nightmare of being heard but unseen. For children, the world of adults often feels just like this: unpredictable, loud, and impossible to understand. The Janitor’s lair externalizes that anxiety through spatial design.

The Kitchen: Industrial Horror and the Machinery of Consumption

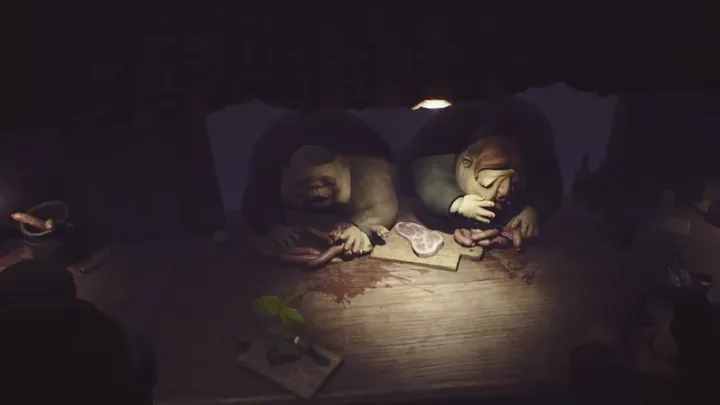

When Six enters the Kitchen, the architecture transforms again—this time into a mechanical labyrinth of grotesque function. Oversized stoves, hanging meat hooks, and giant sinks turn the domestic into the monstrous. The space mirrors the workers who inhabit it—the grotesque twin Chefs—whose world revolves around endless cooking and consumption.

The layout of the Kitchen is circular and repetitive, a spatial metaphor for routine. You sneak past the same areas repeatedly, witnessing how industry turns bodies and food into indistinguishable products. Architecture here becomes a metaphor for mechanized hunger.

The attention to scale is crucial. Counters tower over Six like cliffs, pots are large enough to drown in, and the environment seems purposefully built to remind you of your insignificance in this machinery of gluttony. It’s not just a kitchen—it’s a factory of indulgence, where the very design mocks the player’s smallness.

The Guest Quarters: Architecture of Decay and Desire

As the game progresses, the Guest Quarters expand the themes introduced in the Kitchen. Long corridors filled with groaning, mask-wearing diners portray a world collapsing under its own appetite. The rooms are barely functional—chairs toppled, tables overloaded, walls cracked.

The architecture here begins to reflect psychological states rather than logic. Everything feels too close, too suffocating, too excessive. The verticality of the level design forces players to climb, crawl, and squeeze between bloated figures, transforming navigation into an act of desperation.

Symbolically, this is the world of adults at its most grotesque: blind consumption with no self-awareness. The crumbling rooms are not just backdrops—they’re manifestations of a civilization eating itself alive.

The Lady’s Quarters: Spatial Minimalism and Psychological Control

In contrast to the chaotic Guest Quarters, the Lady’s domain is austere, symmetrical, and eerily quiet. Every room feels meticulously arranged, a deliberate counterpoint to the earlier excess. This minimalism represents control—a spatial embodiment of repression and perfectionism.

The mirrors, locked doors, and softly lit rooms speak to the Lady’s obsession with image and concealment. Architecture here becomes a psychological fortress. The stillness and order evoke the suffocating calm of trauma’s final stage: denial.

The most telling architectural feature is the pervasive symmetry. The Lady’s quarters reject the chaos below, but that rejection creates its own horror. Perfection becomes prison; stillness becomes silence. The player senses that this space is built not to live in, but to hide within.

Vertical Movement as Emotional Progression

Throughout Little Nightmares, verticality serves as a narrative language. Six begins in the depths and ascends gradually toward the surface, mirroring an emotional climb from repression to awareness.

The game’s architectural transitions—elevators, ladders, ventilation shafts—mark stages of psychological growth. Each vertical shift signifies a confrontation with a deeper form of fear: from the primal (darkness, confinement) to the existential (identity, morality).

Even the final confrontation with the Lady takes place at the highest point, suggesting transcendence through understanding. The climb is both literal and symbolic: an escape from oppression and an ascent toward painful enlightenment.

Lighting and Shadow as Architectural Texture

Light and shadow in Little Nightmares are not decorative; they are structural elements. Corridors are defined as much by what they hide as by what they reveal. The interplay of darkness and illumination builds tension but also communicates emotion.

Shadows create intimacy and terror simultaneously. They shrink spaces, forcing the player into claustrophobic awareness, but they also provide refuge—a safe void. Light, on the other hand, exposes and punishes. The game’s architecture manipulates these contrasts to evoke emotional unease.

This use of light as structure rather than atmosphere elevates Little Nightmares to a form of psychological architecture. You don’t just move through rooms—you move through gradients of emotional exposure.

Sound and Space: The Architecture of Silence

The Maw is filled with subtle ambient sounds—dripping water, metal groans, distant footsteps—that give its architecture a pulse. This soundscape defines the spatial experience as much as visual design.

Every echo reveals the shape of the room, every thud gives dimension to the unseen. The silence between sounds becomes the architecture’s breath. It’s this auditory emptiness that gives Little Nightmares its dreamlike quality—where fear is not just seen, but heard.

Symbolically, silence in the game mirrors the voicelessness of childhood trauma. The player, like Six, navigates a world where speaking is impossible, and space itself becomes the only means of expression.

Architecture as a Reflection of Power and Consumption

By the end of Little Nightmares, the player understands that The Maw’s architecture is not random. Each section represents a social stratum within a hierarchy of consumption. The Prison houses the powerless, the Kitchen serves the indulgent, and the Lady’s Quarters rule over all. Architecture defines status.

This vertical hierarchy is not just spatial but ideological. The higher you climb, the more pristine the environment—and the more corrupt its meaning. The Maw becomes an allegory for systemic exploitation, its architecture a visual essay on inequality.

The game’s genius lies in making players feel this system physically. Every jump, crawl, and climb becomes a confrontation with the structures of oppression. In this sense, architecture becomes not just setting, but story.

Conclusion

The architecture of Little Nightmares is one of the most sophisticated examples of environmental storytelling in modern gaming. It transforms walls and corridors into instruments of emotion, turning the player’s journey into a conversation between fear and understanding. Each space holds psychological weight, guiding Six—and the player—through a symbolic narrative of oppression, hunger, and liberation.

To understand Little Nightmares is to learn its language of space: the way a slanted wall conveys anxiety, or how a silent corridor reflects repression. Through its architecture, the game does what few stories dare—it turns trauma into place, and fear into form.